Jul 17

2014

The Scajaquada is a crippled creek

Municipalities dump more than a half billion gallons of sewage mixed with untreated stormwater into the creek annually. That putrid cocktail has fouled the creek’s water in a variety of ways.

Sludge composed of decaying human feces and other contaminants is up to five feet deep in places along the creek bottom.

Fecal bacteria is present at levels up to 20 times higher than what’s considered safe for recreational use.

Avian botulism, which has paralyzed and eventually killed hundreds, if not thousands of birds over the years, lurks in a stretch that cuts through Forest Lawn Cemetery and Delaware Park.

And if that’s not enough, the Scajaquada empties into the Black Rock Canal, which is used by boaters, fishermen and crew teams.

“There’s no doubt that Scajaquada Creek is probably a horror story of what not to do to a creek,” said Jill Jedlicka, executive director of Buffalo Niagara Riverkeeper.

Indeed, the Scajaquada is a man-made disaster, and has been for more than a century.

A 3.7 mile stretch through Cheektowaga and the east side of Buffalo was covered in the 1920s because the water was rank from sewage and industrial pollution. Wetlands that used to filter pollution have been largely built on and paved over.

“You can’t do much more to a creek that we have done as a society to Scajaquada,” Jedlicka said.

View a photo gallery of the creek shot by WGRZ’s Francesco Ardito

Investigative Post interviewed nine sources with knowledge of the Scajaquada and obtained a half-dozen reports and hundreds more pages of documents, some through the state Freedom of Information Law.

These interviews and documents underscore not only the problem, but the daunting challenge municipalities face since the federal Clean Water Act was adopted in 1972, which made most of these sewer overflows illegal. Although work and planning is underway to significantly reduce the sewer overflows, it may be decades before cities, towns and villages comply.

Wetlands destroyed

The 15-mile creek originates in Lancaster from a natural spring and meanders west through Depew, Cheektowaga and Buffalo, where it flows into the Black Rock Canal and Niagara River. Thirty more natural underground springs, including the city’s original water supply Jubilee Springs, recharge the creek in Forest Lawn Cemetery.

Scajaquada Creek reappears from an underground tunnel in Forest Lawn Cemetery near Main Street. (Courtesy Mark James II)

Burying the 3.7 mile stretch of the creek in Cheektowaga and East Buffalo in the 1920s was followed by more modifications, including diverting and straightening about a third of the creek in the 1970s, to control flooding.

The Army Corps of Engineers warned before the work started that it would “destroy and disturb the natural terrestrial and aquatic ecosystem, have long-lasting effects upon the environment and encourage further floodplain development” according to a Buffalo Niagara Riverkeeper 2002 report.

That it did.

Sprawl has wiped out most of the Scajaquada’s wetlands that previously filtered out contaminants in the same way a Brita pitcher cleans tap water.

The biggest culprit was the construction of Walden Galleria, the region’s largest shopping mall that opened in 1989, destroying 65 percent of the creek’s wetlands. Now, only 2 percent of the creek’s 18,590-acre watershed are wetlands, according to a Buffalo Niagara Riverkeeper report, well below what’s considered an acceptable threshold.

“The wetlands were seen as a nuisance and they were either filled in, dredged out or paved over,” Jedlicka said.

Sewage dumped into creek

The biggest reason the Scajaquada is so badly polluted these days is because Cheektowaga, Buffalo, and to a lesser degree, Depew, dump more than a half-billion gallons of untreated sewage mixed with dirty stormwater into the creek every year. These overflows usually happen when rain or snow melt overtaxes the sewer systems.

Buffalo’s system, called a combined sewer, collects stormwater, sewage, and industrial wastewater in the same pipe for treatment. These types of sewer systems are no longer built.

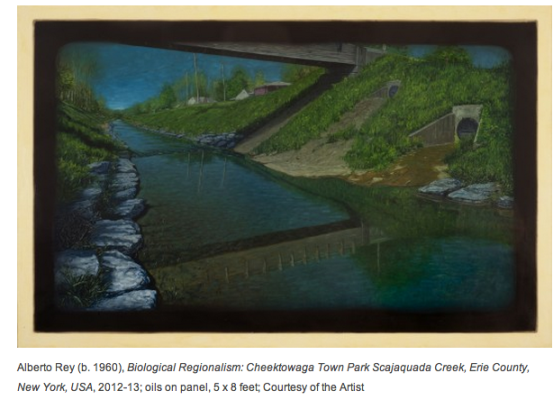

I found that the amount of E. coli in the water was astounding.

—Alberto Rey, artist and professor

In Cheektowaga and Depew and most other local suburbs, sewage and industrial wastewater are separated from stormwater, which is never treated but rather routed from street drains into the nearest waterbody.

Regardless of the type, “these systems were designed intentionally to overflow sewage into our waterways so they don’t back up into basements or into businesses,” Jedlicka said.

Overflows happen frequently—283 times in Cheektowaga over 12 months ending this past May. That’s more often than any similar sewer system in the state, according to data collected under the Sewer Pollution Right to Know law.

Cheektowaga last year reported 487 million gallons of sewer overflows, more than two-thirds of which reached the Scajaquada. Depew reported 5 million to 10 million gallons of sewer overflows into the creek.

The sewer pipe to the left spews about 270 million gallons of raw sewage into the creek in Forest Lawn Cemetery.

Cheektowaga contracts with the Buffalo Sewer Authority to treat most of its sewage. Experts interviewed by Investigative Post weren’t sure how much, if any, of the town’s overflows are prevented from reaching downstream by the city’s complex sewer system. Sewer Authority officials refused to answer questions.

These overflows are illegal under the Clean Water Act, but they occur frequently in this region. Thus, 10 municipalities in Western New York are under enforcement orders with the state Department of Environmental Conservation to develop plans and timelines to stop the overflows, including Cheektowaga and Depew.

In addition, the number of overflows from a single pipe in Buffalo can reach 65 a year. The volume spewed is nearly 270 million gallons of raw sewage from one pipe alone in Forest Lawn Cemetery. In addition, four more pipes downstream spew raw sewage into the creek at far lesser volumes.

Left behind is an unmistakable odor in the cemetery that offends visitors.

“The creek has an ability to calm and soothe, and in a cemetery those are very important qualities,” said Joseph Dispenza, president of Forest Lawn Cemetery. “And when one approaches the creek and finds an odor offensive, it detracts from the soothing, healing, cathartic environment.”

Sludge and other pollutants

The sewage pollution has landed the Scajaquada on the DEC’s impaired waterways list—a designation assigned to only six percent of the total river and stream miles assessed by the department. This means the creek does not meet water quality standards and is regarded as too polluted for recreation. The Scajaquada is the only waterway in the Niagara River watershed deemed unfit for aquatic life by the DEC.

Sewage sludge up to five feet deep blankets portions of the creek’s bed, according to a DEC memo from August 1993. The fecal bacteria levels can be so high in portions of the creek that water testing devices are maxed out.

“I found that the amount of E. coli in the water was astounding,” said Alberto Rey, a SUNY Fredonia professor and artist whose Scajaquada Creek exhibit this spring at the Burchfield Penney drew wide acclaim.

The sludge provides an excellent medium for the avian botulism toxin. Although this version of the toxin does not pose a danger to humans, it kills infected waterfowl. Before death, the birds are so sick that their necks go limp and their legs are paralyzed, forcing them to walk with their wings.

DEC officials reported hundreds of dead birds in both Cheektowaga and Buffalo since the 1970s, with major outbreaks in the 1990s. Smaller numbers of dead birds suspected of botulism pop up almost annually, Jedlicka said.

I think there’s a general feeling that we can’t treat creeks like trash dumps anymore.

—Margaret Wooster, author and environmental activist

The “hot spot” in the creek spreads a third of a mile from a point near Hoyt Lake to a section in Forest Lawn Cemetery just past Delaware Avenue, according to a DEC memo.

The only way to get rid of the toxin is to dredge. That’s exactly what the DEC ordered the Buffalo Sewer Authority to do in November 1993 by emergency order. But the sewer authority never performed the work.

“I believe the reason was that removal was to [sic] costly for the City to undertake,” wrote DEC’s senior wildlife biologist Kenneth Roblee in a July 1996 email.

Buffalo Sewer Authority officials, including General Manager David Comerford, refused numerous interview requests regarding the Scajaquada.

In addition to botulism outbreaks, a 1996 study found the now-banned chemicals PCBs in creek fish. Young fish in the Scajaquada had the highest levels of PCBs in the Niagara River watershed, the report said. The amount was enough to pose a “severe threat to fish-eating consumers.”

Improvements planned

Federal and state regulators have been slow to enforce anti-pollution laws and regulations, but some improvements are in the works.

“I think there’s a general feeling that we can’t treat creeks like trash dumps anymore,” said Margaret Wooster, author of the book “Living Waters-Reading the Rivers of the Lower Great Lakes” and an environmental activist involved with research and cleanup efforts on the Scajaquada for 25 years.

Updating sewer systems to stop overflows is a national dilemma, especially in the Great Lakes states, which need an estimated $100 billion in fixes. A third of that is needed in New York.

After 15 years of negotiations with the Environmental Protection Agency, the Buffalo Sewer Authority agreed to an enforcement order to spend $380 million on sewer projects over the next two decades. About $91 million will be spent on fixes for the Scajaquada, with one-third going to experimental green infrastructure projects, such as rain gardens and pavement that allows water to pass through, to keep millions of gallons of stormwater from reaching the sewer system.

But the three projects with the biggest impact on preventing overflows into the Scajaquada aren’t scheduled to be finished for 13 to 16 years.

Even with the work, an estimated 52 million gallons of sewer overflows a year are expected to flow into the Scajaquada, according to the sewer authority’s plan.

Meanwhile, Cheektowaga officials say they are still waiting on the DEC to approve its engineering plans.

“The town has filed a report approximately 4 years ago and are waiting for a response,” said Cheektowaga Supervisor Mary Holtz in an email.

However, a spokesman for the DEC said in an email Wednesday that the department informed Cheektowaga officials in August 2010 that the town’s plan “was not acceptable.”

Still, the town recently spent about $1 million on a project that prevents 3.4 million gallons of sewer overflows from reaching the creek, among other work.

“I could have the most optimistic approach, but it boils down to financing, your ability to afford it and keep taxes realistic,” said Cheektowaga Town Engineer William Pugh.

All this means the Scajaquada faces the prospect of several more decades of harm before it might see cleaner waters. Until then, Wooster will continue to refer to the creek as a “Frankenstein monster.”

“Yet it is amazingly still alive,” she said.