Nov 1

2012

Recycling: City Hall’s bin is less than half full

Editor’s note: This is a three-part series. Today’s story examines the city’s recycling program. Friday’s report, which will also be the subject of coverage on WGRZ, looks at recycling efforts in the city’s public schools. On Monday, we look at the wildly success recycling program in San Francisco.

City Hall’s halfhearted efforts to increase its anemic recycling rate is plagued by a failure to enforce laws, educate the public or act on a host of recommendations, Investigative Post has found.

The result: Buffalo’s recycling rate is less than half the national average, costing Buffalo taxpayers more than $1 million in potential savings.

“We’ve never reached our potential and that’s the frustration. We could have done a lot better. We can do more,” said Fillmore Common Council Member David Franczyk.

A new green tote program that allows residents to place all recyclables in one container has increased Buffalo’s dismal curbside recycling rate to about 16 percent this summer. But there has been slippage since.

“We haven’t sustained a 16 percent level,” said Public Works Commissioner Steven Stepniak. “Those are peak months. It’s anywhere in the range of 12 to 16 percent on a general basis.”

Meanwhile, numerous proposals calling for incentives, enforcement and education to boost recycling rates haven’t gotten past the talking stage.

An Investigative Post examination of City Hall’s recycling efforts found:

- Recycling rates are well below the national average of 34 percent for both residential and commercial collections. Buffalo’s recent fluctuating rate of 12 to 16 percent only takes into account houses, apartments and businesses that participate in the city’s program, which city officials maintain could be as high as 90 percent, but which some Common Council members say is substantially lower in their districts.

- Buffalo is not enforcing its own multi-residential and commercial recycling laws. Many business owners and property owners aren’t even aware of the mandate. By failing to mandate recycling for single-family residences, Buffalo’s local law only partially complies with state law.

- City Hall hasn’t replaced the full-time recycling coordinator who left in 2009, even though funding for the job is budgeted. Most of the work has now been assigned to the son-in-law of one of the mayor’s staunchest political allies on Common Council, whose previous job with the city was as a seasonal clerk in Public Works.

- The city’s low recycling rate has cost consequences. The combination of reduced landfill fees and rebates for recycled materials could save the city more than $1 million annually if its rate was closer to the national average. Those savings could potentially lower the city’s unpopular user fee charged to collect trash or allow the city to offer incentives to encourage more recycling.

- Buffalo is not following terms of its contract with private recycling hauler Allied Waste-Republic, which provides annual spending of $105,000 on recycling promotion and education. The city is spending little of that money on educational programs.

- The administration has largely ignored recommendations on how to improve recycling made by auditors in the city comptroller’s office, citizen groups and Council members.

Stepniak said recycling is “important to the city” and that improving the recycling rate is a top goal of the Brown administration.

Rolling out the green totes was phase one. The second phase beginning now is to introduce the green totes into the school system with an educational program. The final phase will be extending the green tote program to more businesses, along with an outreach program.

Stepniak said by this time next year, he hopes to have the recycling rate at about 20 percent. Anything less would be deemed a failure.

“At this point going forward, we are going to make adaptations as needed. And I think maybe in the past that didn’t happen,” Stepniak said.

Buffalo’s roller-coaster rate

Franczyk brought noted biologist Barry Commoner to Buffalo in the late 1980s in an effort to to help create a robust recycling and solid waste program. At the time, the city collected its own trash and recyclables through the Sanitation Department.

Franczyk said the result was a comprehensive and simple plan for intense recycling that would have boosted the city’s recycling rate to 50 percent. The plan sought a 90 percent participation rate among residents and an Office of Recycling that included two support staff members, a recycling educator and a recycling coordinator.

The report also recommended 36 new employees, broken down evenly in truck drivers, laborers and sanitation workers.

“[Commoner] designed a Cracker Jack plan. He gave us the roadmap and it ended up in a drawer,” Franczyk said. “We spent a lot of money on that.”

Recycling rates increased to no more than 14 percent by the mid-1990s, but participation was mostly in more-affluent neighborhoods, Franczyk said. The rate increased when the city hired Ed Marr as the director of refuse and recycling, but Franczyk said he was later reassigned to implement a user fee for trash collection.

“There was some education at that time, but he was hired for one reason and then he was put in another direction,” Franczyk said.

Marr, now the executive director of Greater Greenville Sanitation Commission in South Carolina, said he was always being pulled in different directions, which impacted recycling education programs.

“You can’t just send them a postcard and say, ‘Hey, recycle.’ You have got to hit them time and time again,” Marr said.

While recycling rates grew nationwide to about 30 percent by 2000, Buffalo’s rate dropped, bottoming out at 7 percent in 2003. Franczyk said City Hall just didn’t take recycling seriously.

“The Commoner report gave us a goal,” he said. “Even if we reached 30 percent and not 50, we would be doing great. I can’t think of any good reason why we wouldn’t follow it.”

Participation rates began to inch up after the city partnered with Erie County in 2003 for a $179,677 matching state grant for a three-year recycling education project. But the 12 percent goal set for 2006 was not achieved. Nevertheless, the contract was extended through the end of 2009.

City residents were asked to recycle paper separately from glass and plastic in separate blue bins. To make it easier, city officials in 2008 first discussed introducing totes that would enable residents to place all recyclables in a single container. It took more than three years to roll out the new green totes to residents. Other city initiatives launched in recent years include a electronics recycling program and curbside collection of yard waste.

More than 70,000 green totes were delivered to city residents in December 2011. In April, Brown and Stepniak held a press conference to tout the success of the program and announced that Buffalo set a new recycling record in March with 1,000 tons of recycled material, up 300 tons from the prior month.

The recycling rate, they said, had jumped to 16 percent.

“Those seem to be working,” Franczyk said of the new totes. “The numbers are going up. I want to see more hard numbers.”

Reasons to recycle

There are numerous advantages to recycling, including reducing pollution, creating jobs and saving energy and natural resources.

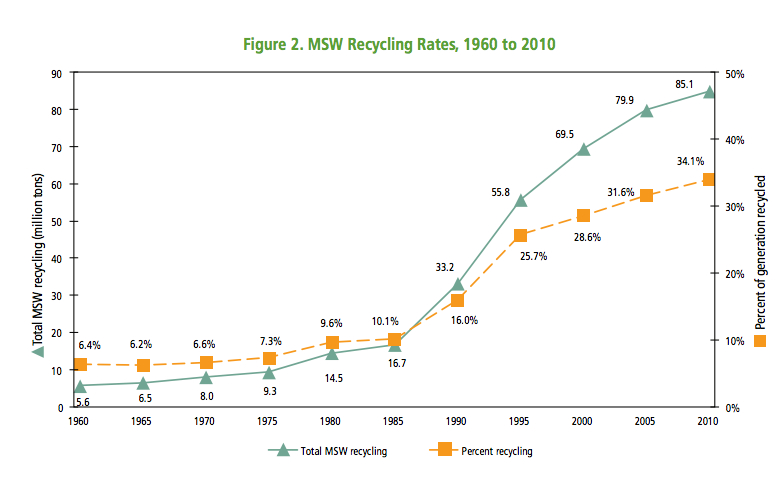

Recycling at the national level had taken off since the mid-1980s, with rates increasing from about 10 percent to 34.1 percent in 2010. That’s the equivalent to taking 25 million cars off the road, according to the Partnership for the Public Good, a local group that provides research and advocacy on a range of community issues.

Recycling also saves the city money. For example, the Brown administration announced in September that since January 2012, the city made $105,142 and saved $515,000 through a combination of the sale of recycled materials and landfill tipping fee savings.

Andy Goldstein, the city’s last recycling coordinator, who is now environmental educator for Cascades Recovery, said during an October 2 radio broadcast last month on WUFO-AM that the city is moving in the right direction with the green totes, but that momentum needs to continue. He believes the city’s recycling gains will drop again if there aren’t constant reminders and education.

“There is still more to do,” Goldstein said. “It is always a constant message that you need to put out to the residents.”

In February, the city issued a request for proposals for a marketing campaign for its green tote recycling program with a budget of $75,000. The city was looking for a program that included school posters and other educational materials for the schools, mailers, social network presence and mascots. The program was supposed to start in June, but the city rejected the three bids.

Stepniak said he hasn’t decided if the proposals will achieve his goal of establishing a citywide outreach program.

“We’re just not sure how that fits in going forward,” he said about the RFP proposals.

No enforcement

Buffalo mandates recycling for businesses and multi-family dwellings, but does not enforce those requirements.

The City Charter does not mandate recycling for one- and two-family residences even though state law appears to make that requirement.

The city charter requires that multi-family complexes and businesses recycle newsprint, paper, magazines, cardboard, glass, plastic and aluminum containers, metal cans and wood waste. The city charter also requires multi-family complexes to have collection areas for recyclables. Fines range from $25 to $250.

Yet Delaware Common Councilman Michael LoCurto said the city has never enforced its recycling laws or imposed fines on any business or multi-family property managers for noncompliance.

“Right now, there’s the mandate, but not the enforcement piece or an incentive piece,” he said.

Stepniak told the Council in January 2011 there there should be ramifications for those who are not recycling. But he conceded then that the city isn’t doing anything about it.

During an interview on October 24, Stepniak said he’s still not ready to begin enforcement efforts until an educational piece is in full force.

“We felt that education was going to be the way to go, get a solid program that the citizens can be happy with first, and then get into the issues of enforcement at a later date,” he said.

Stepniak wouldn’t say if he is considering hiring more employees to work on improving the recycling rate and enforce the charter.

“We have no city employees assigned to recycling,” said Bill Travis, the president for AFSCME Local 264 and AFSCME Council 35, which represents 550 city employees, including those in the Street Sanitation Department.

Joseph A. Gardella, professor of chemistry for University at Buffalo and member of the Buffalo Environmental Management Commission, said Stepniak told the commission earlier this year that the city was working on an enforcement plan for commercial and multi-family complexes, but he has not seen anything yet. He also said enforcing the mandate with financial penalties could be counterproductive in less affluent neighborhoods.

“There is no clear path to getting enforcement,” Gardella said.

Getting multi-family building managers to recycle continues to be a challenge without any enforcement or education. These buildings are required by city charter to have separate recycling centers, but there is no city-run effort to ensure all do, and many don’t.

“This is often the hardest, even harder than schools, is to get the city to enforce its own laws about apartment buildings having to recycle,” said Goldstein, the former recycling coordinator.

“They are by law; there is an ordinance that says they must recycle. But again, without somebody hitting that apartment building, pushing it, calling up the managers of that apartment building, you are not going to get very far,” he said on WUFO.

Dawn Timm, Niagara County’s environmental coordinator, said she isn’t aware of any municipality or planning unit that aggressively enforces recycling laws in Western New York, but not all mandate it like in Buffalo. She said it seems like a hollow ordinance and that education, advocacy and incentivizing people to throw away less would be a better use of energy than “heavy-handed” enforcement.

“We are not at a point where we need recycling police,” she said.

Other shortcomings

The city is also not following a contractual obligation to educate the public on recycling.

Buffalo’s contract with Allied Waste-Republic for recycling collection includes a rebate of $105,000 a year to fund recycling education and promotion.

But an audit by the city comptroller in 2009 found the city used most of this money to purchase recycling bins. Only $4,821 of $116,276 collected in 2006 and 2007 was used for education and promotion. Stepniak confirmed that the city is still not spending the funds, but did not detail how the money has been used or how much is in reserve.

The city has yet to institute a recycling education program, but Stepniak said he is planning to spend at least $100,000 annually on a program.

“The education piece is coming,” he said. “Using the schools as your catalyst — that’s a big deal,” Stepniak said.

The city is also coming up short on meeting state mandates.

Buffalo last filed in 2008 a required report called the Annual Planning Unit Recycling Report, which details how many recyclables had been recovered for the year, how much waste had been disposed and the destination facilities. The last report filed by the city was from Goldstein, the previous recycling coordinator. (Correction: The DEC said on Nov. 7 that the city actually filed an Annual Planning Unit Recycling Report in May and the incorrect information that the agency initially provided Investigative Post in September was “likely due to internal processes.”)

“The city has indicated that they are working on updating a current annual report, but it has not yet been received by DEC,” said Megan Gollwitzer, a spokeswoman for the Department of Environmental Conversation.

Recycling mandate an enigma

Business owners and property managers who spoke with Investigative Post said they were unaware of the recycling mandate.

Sarah Schneider, co-owner Merge at 439 Delaware Ave., said she was unaware that the city mandates that all businesses recycle, but that her restaurant does it of its own volition.

“We’ve been recycling since we opened and it was kind of a hassle to get the bins. It is just something I thought we should do,” Schneider said. “We do compost. We fill five-gallon buckets and I take them home a couple times a week. We have a little farm for the restaurant in Hamburg.”

Schneider said she approached the city last year with members of the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo with ideas on how the city could better incorporate businesses into its recycling program. She said those ideas were well received, but hasn’t heard back from anyone.

Mike Gott, facilities manager for the Liberty Building and Main Place Mall in downtown Buffalo, said the property is under contract with a private hauler to pick up garbage and recyclables. He said he has never heard of any fines being issued to private businesses for not recycling and he’s never heard of any city requirements or mandates. But they do recycle and any trash the building does have is hauled to Covanta Niagara Company, where they use it to generate electricity.

Sarah Bishop, executive director of Buffalo First, which represents locally owned small businesses, said none of the business people she has spoken with is aware of the city’s recycling mandate.

“Neither the city nor the county have ever spoken to them about recycling,” Bishop said.

“More or less, Main Street business owners don’t feel they have the proper knowledge or tools to either hold the property owner or the city responsible for recycling at their place of business. Again, many do it of their own volition.”

Stepniak said his department has discussed door-to-door campaigns, something that proved to be very successful in San Francisco.

“This is a process and this is going to take some time,” Stepniak said.

Ideas shelved

The city comptroller and a citizen’s commission have issued recommendations to the Brown administration in recent years that have been largely ignored.

In 2009, the comptroller issued an audit that found:

- Buffalo was improperly using recycling education funds for unrelated projects.

- The partnership with Erie County failed to reach its goal of improving the city’s recycling rate to 12 percent and that almost 60 percent of the grant was used to pay the salary and benefits of the former recycling coordinator.

- Buffalo lacks data that can help it target areas where recycling needs to improve.

The audit recommended:

- Developing a better model to statistically track household participation so the city can determine the level of investment needed to improve recycling rates. The tracking system should show rates by district so the city can target areas that have lower rates. The city subsequently added tags to the totes that transmit radio frequencies to track the weight of the tote, but the data is not distributed.

- Making a concerted effort to increase residential and commercial awareness of the importance of recycling. No initiative has been launched.

- Hiring a full-time recycling coordinator to create an aggressive recycling program. No coordinator has been hired.

- Offering an incentives program. No incentives have been offered.

In May, the Buffalo Environmental Management Commission passed a resolution urging the Brown administration to act on six recommendations. The City Charter charges the commission with advising the mayor and Common Council with oversight and guidance of environmental programs.

The commission recommended:

- Hiring a full-time recycling coordinator immediately.

- Revising recycling ordinance to comply with state law by clearly requiring single-family residences to recycle.

- Reminding businesses and multi-family property owners that recycling is a mandate and enforcing the law once those reminders are issued.

- Ensuring all permitted public events have adequate recycling facilities.

- Appointing a Recycling Advisory Panel as a subcommittee to the commission and asking the panel to develop a plan for other recycling programs.

On top of this, Franczyk filed a resolution earlier this year urging the Brown administration to resurrect the city’s Solid Waste Advisory Board that was created in 1997. He said the members’ terms—outside of elected officials and the commissioner of Public Works—have expired. Franczyk said the board hasn’t met in nearly a year. He urged the mayor to appoint five members, but said his resolution has been ignored.

“The charter says you are supposed to have it, but the real reason is you want to make sure recycling is done properly and we want to promote it,” he said.

Groomed for the job

There is wide agreement that the city should hire a full-time recycling coordinator to succeed Goldstein, who left the job in 2009. And the city budget includes approximately $54,500 for the position.

Although Brown and Stepniak have opted not to fill the job until now, the vacancy was posted on October 26, two days after Stepniak was interviewed for this story. Applications are due by Nov. 9.

In the meantime, Paul Sullivan, director of sanitation, has handled some of the recycling work. In turn, Raymour P. Nosworthy, a clerk in the public works department, was appointed special assistant to the public work commissioner in 2009.

John McGoran, the manager of municipal services for the city’s waste hauler Republic-Allied Waste, said Nosworthy has been the city’s point of contact on recycling matters for the past six months.

Nosworthy, a graduate of the Rochester Institute of Technology, started his career in City Hall as an intern in 2007 for University District Common Councilwoman Bonnie Russell. He later worked as a seasonal clerk in the Public Works Department.

In 2009 he was appointed special assistant to the commissioner in Public Works. His pay jumped from $11.11 an hour to $34,133.

Later that year, Nosworthy married Russell’s daughter. The mayor officiated the marriage.

“There’s your connection,” Franczyk quipped.

Stepniak declined to say if he intended to promote Nosworthy in the job or hire someone else for the position. He acknowledged that Nosworthy, who now earns $36,212, had no previous recycling experience prior to his promotion to special assistant, but denied that political connections played a role in his appointment.

Stepniak said Nosworthy has strong work ethic and that he’s had employees climb the ranks with less education who became “superstars” in his department.

“You can have a lot of education, but not have that passion. He’s got the passion,” Stepniak said.

Nosworthy said he is applying for the recycling coordinator job and believes he is qualified because he has spent the past three years working closely with Public Works officials on the recycling program. Before coming to Buffalo, Nosworthy did not have any experience with recycling programs.

“I didn’t just fall out of the sky just because I am on good terms with the mayor,” Nosworthy said.

The chief reason Buffalo’s recycling rate hasn’t reached its potential is because public education has not been consistent, said Sam Magavern, co-director of the Partnership for the Public Good.

“Mainly, it requires continual public education and reminders,” Magavern said. “Once residents understand not just the environmental benefits but also how it saves taxpayer money, we think they will recycle more. Once businesses understand that it can save them money and that it’s legally required, they will recycle more, too.”