Jul 23

2015

Child abuse unit still struggling

Kim Henderson lasted a year as a caseworker investigating allegations of child abuse and neglect.

She was assigned more cases than she felt she could handle. Many of the cases she inherited were poorly documented. And many of the families she was assigned to work with hadn’t seen a caseworker in months.

Henderson quit her job with Erie County Child Protective Services two weeks ago, worried that too many families with children at risk weren’t getting the help they needed.

“Sometimes the kids hadn’t been seen for months on end – it was terrible,” she said.

Henderson’s experience is not unique among the more than 130 caseworkers employed by Child Protective Services. A two-month investigation by Investigative Post found the department, which has been under increased scrutiny over the past three years after the deaths of three children on its watch, continues to be plagued with serious problems.

Key findings include:

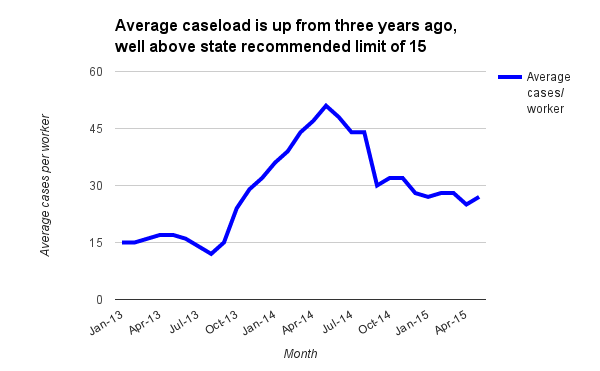

- Caseloads have jumped over the past two years from an average of 15 to 27 per caseworker, which is nearly double the workload recommended by the state. The average caseload has fallen from its peak of 51 in May 2014, however.

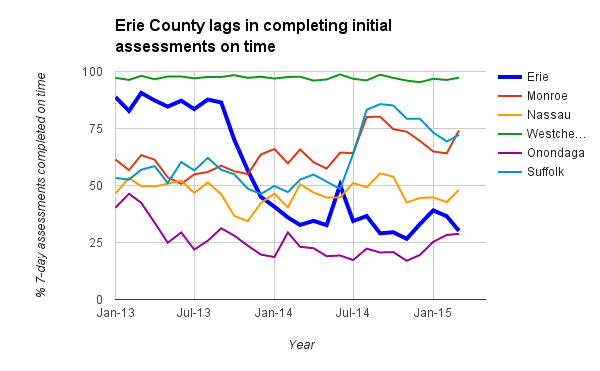

- CPS is failing to meet state-mandated deadlines for completing preliminary assessments of abuse and neglect complaints nearly two-thirds of the time. The on-time completion rate was 79 percent in 2013; since then it’s been less than half that rate.

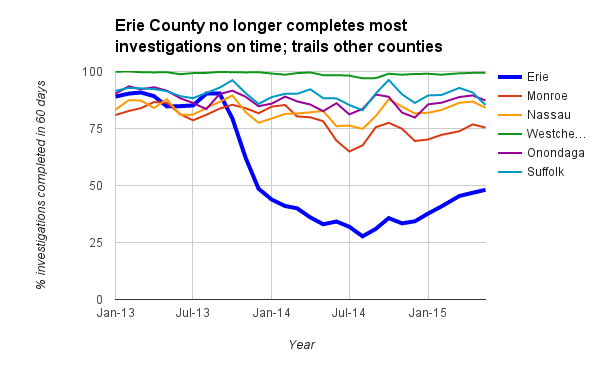

- Similarly, the on-time rate for completing investigations has dropped from 92 percent in 2012 to 44 percent this year.

- Erie County’s on-time completion rate is by far the lowest among counties the state considers statistically comparable.

- The 133 caseworkers currently available to investigate complaints, while up from two years ago, is short of the 151 that Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz has pledged.

The numbers notwithstanding, Erie County Social Services Commissioner Al Dirschberger said, “We’re on a really good path to be where we want to be as a department.”

“You can’t just look at the numbers. We have to look at the story behind the numbers.”

But that story, according to 12 current and former CPS workers interviewed by Investigative Post, is one of sleepless nights, impossible workloads and endless missed visits to families.

Their main concern: Mounting caseloads compromised their ability to keep families safe.

“The caseloads mushroomed to where it was unmanageable,” said Duane Dunaj, a veteran supervisor who retired last November.

Most of the dozen caseworkers interviewed said the department has been functioning no better in recent months than before the state intervened in September 2013.

This story is based on documents and data obtained from state and county social services agencies through seven Freedom of Information requests, as well as interviews with 22 people, including social services administrators, current and former CPS workers, child welfare advocates and families who have had cases with CPS.

Poloncarz, who has made reforming CPS a priority, refused an interview request.

Skyrocketing caseloads

CPS workers were assigned an average of 27 cases in May this year, according to figures the Department of Social Services provides to the Erie County Legislature. The state recommends a caseload of no more than 15 per worker.

Caseloads were close to that recommended level until the September 2013 death of five-year-old Eain Clayton Brooks – whom CPS workers decided was safe at home despite numerous reports of abuse – triggered an unusually intensive state review of CPS. The state examined all 894 open CPS investigations.

The thoroughness of the audit had an unintended consequence: the county was not allowed to close cases while the review was underway. That created a backlog. In addition, the more-thorough investigations recommended by the state meant that cases took longer to close.

Caseloads skyrocketed in the months following the audit, peaking at an average of 51 in May 2014. Some workers were handling up to 90.

“When you have 90 cases, you’re not going to remember the kids’ faces, let alone their names or their needs or their medical histories,” one former caseworker said.

Over the past two years, CPS has added 32 caseworkers and supervisors and 12 part-time investigators. Those hires have helped cut the number of cases assigned to workers almost in half since this time last year.

But the average workload remains much higher than it used to be. As recently as May, one in seven caseworkers were assigned at least 45 cases – triple the maximum workload the state recommends.

Such a heavy workload “is unacceptable. We’ve said that all along,” said Lynn Dixon, chairman of the County Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee, which oversees the Department of Social Services.

Dirschberger, the commissioner, maintains that only a few caseworkers still have high caseloads and that he expects a “significant” decrease in caseloads by the end of the summer. He also said overstretched workers will be assigned fewer new cases until their workload has been reduced.

There is, however, widespread skepticism among CPS staff regarding the caseload figures. All 12 of the current and former workers interviewed said they believe average caseloads had been – and continue to be – significantly higher.

“The average caseload was not 27 in May – no way,” said Henderson, the former caseworker.

Missed deadlines

One consequence of the mounting caseloads was that workers began missing deadlines.

Under state law, caseworkers have seven days from the filing of a complaint to complete an initial assessment of whether children are in any immediate danger. CPS completed 79 percent of those assessments on time in 2012 and 2013. That number dropped to 35 percent last year and stands at 36 percent for the first five months of this year.

“The seven-day assessment is the quick and easy one,” said Ashtin Penelton, a former caseworker who was fired in October 2014. “If that’s not being done on time, it’s because of the caseloads.”

The state also requires that investigations be completed within 60 days of a complaint being filed. Workers completed 92 percent of investigations on time in 2012. That completion rate dropped to 35 percent in 2014 and has increased to 44 percent for the first five months of 2015.

Erie County’s on-time completion rates are much lower than comparable counties upstate and on Long Island, where rates of 70, 80, and 90 percent are the norm. For example – Monroe County, which includes Rochester – is completing investigations on time at almost twice the rate of Erie County.

Sleepless nights

Even with caseloads of 15, child protection is an inherently stressful job.

Workers go into strangers’ houses with nothing more than a plastic badge and a notebook. Most cases require difficult decisions and hours spent entering notes into the state’s notoriously temperamental computer system. Workers must document everything they do: every phone call, every visit, every conversation with a family member, doctor or teacher.

The mounting caseloads inevitably took a toll on workers. They were offered unlimited overtime to tackle the backlog of open cases, but many said late nights, missed lunch breaks and working on weekends became necessary just to keep up.

Dunaj, the retired supervisor, said he used to joke that caseworkers should be given catheters because they barely had time to go to the bathroom.

It wasn’t unusual, workers said, to see colleagues in tears in the corridors, or to hear them sobbing in the bathrooms.

“It’s almost like instead of saying good morning, people talk about how horrible the job is,” recalled LaRusha Blakely, one of the new trainees, who was dismissed in March.

Until last month, workers were supposed to visit families assigned to them at least every 30 days. But with so many cases to manage, workers said they couldn’t make those visits as scheduled. Many workers fell weeks, even months, behind on their paperwork.

“You can’t see 80 families in 30 days,” said Blakely. “You just can’t.”

A policy change implemented in June means that for families deemed low-risk, a phone call or email contact with a child’s teacher, guidance counsellor, or an “unbiased relative” can now replace a home visit.

One former caseworker, who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation, described the months during the winter of 2014 when she was working on 97 cases.

“I was waking up in the middle of the night in a dead panic,” she said. “This broke me.”

A major source of anxiety, the former worker said, was that her workload compromised her ability to investigate each case properly.

“When you have such high caseloads, it’s easy for things to slip through the cracks,” she said. “You miss things you might have seen normally.”

When she asked supervisors for help, “they didn’t want to hear it,” she said. “But I told them: ‘I’m not keeping anybody safe like this.’ ”

She resigned this spring, taking a lower paying job working night shifts at another human services agency.

“I thought our job is to protect kids,” she said. “If we can’t see them, how can we protect them?”

Backlog of cases

When Henderson finished training, she – along with many of the new caseworkers hired last summer – was put to work tackling the backlog of open cases that had accumulated in the wake of the state audit.

While the number of overdue case has been cut almost in half since its peak last June, there were still some 1,600 overdue CPS investigations at the end of May of this year.

Many trainees said they were taken aback by the problems they found in these case files.

“These were cases that had been sitting for months,” Henderson said.

The state’s 2013 review had identified “minimum compliance with the regulatory requirements, rather than thorough and complete assessments” of families as one of Erie County’s weaknesses. But the increased workload made achieving that almost impossible, caseworkers said.

“Often stuff just wasn’t done right at all,” said Penelton, one of the new trainees who did not pass probation.

Scheduled visits had been missed. Progress notes had been started and never finished – or were so brief as to leave the family’s actual situation unclear.

Some families had gone months – even sometimes up to a year – without being seen by anyone from CPS, former workers said.

Families are understandably angry when their cases are left open for so long.

“You have to walk through the door apologizing,” said Blakely, a former caseworker. “They’d say: what do you want? I haven’t heard from anybody in months.”

Some said the cases that were left open tended to be low-risk and, therefore, a low-priority for over-stretched workers, who had to triage their cases. Others saw it differently.

“Just to let a case sit for months, something devastating could happen,” Henderson said.

Short on bodies, experience

Poloncarz, in response to the state’s critical audit, pledged to hire more caseworkers and, in fact, 44 full- and part-time positions have been added in the last year-and-a-half.

But CPS remains understaffed: The county executive has said the department needs 133 workers taking cases to get caseloads down to 15. Due to turnover, however, there were only 122 workers in May taking cases – about the same number as in October 2013, before new workers were brought in.

A shortage of experienced caseworkers exacerbates the problem.

Thirty-five percent of the staff has less than one year’s experience, according to county figures.

Many former workers say it takes at least a year or two to become proficient, and that there are some things you can only learn on the job.

“No one can train you to walk into a dirty house and see kids playing with their own dirty diapers and come out and be the same,” said Kevin White, a veteran caseworker who was dismissed last year.

Dirschberger insists he is not discouraged.

“For us as a department, we’re looking forward, we’re taking a positive spin on this,” he said.

The state audit, he added – despite its negative consequences – “has made us stronger.”

Most of the CPS workers interviewed by Investigative Post disagreed. They said the department has yet to recover from the impact of the state’s intervention.

“When the commissioner is saying, ‘Everything is OK’ – it’s not. That’s not what I see,” said Henderson, the caseworker who left last month.

“Everything is not OK.”